This Toolbox Talk tackles an ingredient that is so fundamental to rolled cookie recipes that maybe it should have been the first in this series. I'm talking about flour, people! Even an ingredient as common as flour has its differences around the world, which impact baking results.

In this post, I examine only "plain" white wheat flour commonly available in grocery stores, i.e., flour containing no added leavening and just the endosperm of the wheat berry and none of the wheat berry's other two parts: bran (the hard outer shell) and germ (the innermost part). In other words, whole wheat, gluten-free/non-wheat, and self-rising flours are not discussed. Further, I give no attention to stone-ground flour or bleaching flour, as both processes seem to merit whole discussions of their own. For a more in-depth discussion of all flour types, please see this article from bonappetit.com.

Within the realm of "plain" white wheat flour, there are various types of flour, ranging from cake and pastry flour to all-purpose and bread flour. Most rolled cookie recipes that I found online indicate which type of flour is required, but don't indicate why this flour is preferred. While LilaLoa doesn't specify the type she uses, many others, including Sweet Sugarbelle, SemiSweet Designs, Honeycat Cookies, and Julia M. Usher, use all-purpose flour. And though Julia doesn't state why she uses all-purpose flour in the one cookie recipe on her site, she does discuss why she uses different flour types in her cookie books. (We'll come to this point in a bit.)

So why is the type of flour important? The trick is that, even while flour is mostly starch, it is its protein content that makes all the difference in baking! You can read a comprehensive explanation of the role of protein in various types of flour on joythebaker.com. In short, here's how I understand it: when liquid is added to wheat flour, it coaxes the two primary proteins in flour (gliadin and glutenin) to combine and form gluten strands (Source: finecooking.com). The more protein in the flour, the stronger the gluten strands become, especially if you work the dough, i.e., by kneading it. Stronger gluten strands are better able to contain the carbon dioxide bubbles formed during baking, causing the dough to rise, and will lead to a coarser "crumb" and chewier texture (think Italian ciabatta bread). A lower protein content means that fewer, weaker gluten strands are formed, allowing the carbon dioxide bubbles to escape before they get too big. In this case, the end product will have a finer crumb and more delicate and tender texture - just what one wants in cakes and pastry crust! Because of their stronger gluten strands, doughs made with high-protein flours tend to be more elastic or stretchy than their lower protein counterparts (think pizza versus cookie dough, for instance). Also, generally speaking, the higher the protein content of the wheat flour, the more absorptive it is, meaning that doughs made with high-protein flour tend to be drier and stiffer too, unless additional liquid is added.

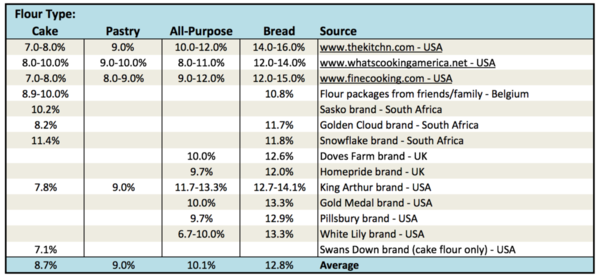

Flour with a relatively high protein content is also called "hard" or "strong" flour, whereas lower protein flour is called "soft" or "weak". The protein level of a particular type or brand of flour is typically determined by a couple of things: the specific variety of wheat, and whether pure gluten or flour of a different protein level has been incorporated, as explained here. As alluded to earlier, the most common types of flour are cake, pastry, all-purpose, and bread. Their respective protein contents can vary by brand and country (and region within a country), as demonstrated to some extent in the table below. But, generally speaking in the US, cake flour has the lowest protein content (7% to 8%, usually), and bread flour has the highest (12% to16%). All-purpose flour ranges between about 9% and 12%. (White Lily brand is the exception, as its 6.7% "all-purpose" flour behaves more like cake flour.)

(Sources: Product packaging and company websites)

With this mini lesson in protein content behind us, most cookiers' choice to use all-purpose flour should now be clear! Because of its middle-of-the-range protein content, all-purpose flour makes cookie dough elastic enough to roll out without falling apart (as can happen when all cake flour is used), but relatively delicate on the palate. Even so, as Julia points out in her books Cookie Swap and Ultimate Cookies, other flour types can also be used with success in rolled cookies, depending on your purpose. Her normal "Cutout Cookie Gingerbread", which she uses for flat cookies and small 3-D constructions, calls for all-purpose flour. But, when she's in need of a more sturdy dough for large constructions, she turns to her "Construction Gingerbread" made with high-protein bread flour. Conversely, for more delicate and crumbly shortbread, she substitutes cake flour for some portion of the all-purpose flour in her usual shortbread recipe.

Flour Around the World

As we saw in the last section, different names for flour often imply different protein contents. However, it does not appear that any one name implies the same protein content from place to place, or even within a country. For example, the protein content of Snowflake brand "cake" flour from South Africa (my neck of the woods) is comparable to the protein content of King Arthur "all-purpose" flour from the US. Likewise, the protein content of Sasko brand "cake" flour, also from South Africa, is comparable to that of Gold Medal and Pillsbury "all-purpose" flours from the US. Further, Snowflake "cake" and "bread" flour have nearly the same protein content (11.4% and 11.8%!), which, again, is closer to "all-purpose" flour in the US.

To eliminate this naming ambiguity, professional bakers often rely on the W index as a measure of flour "strength" or protein content. This index categorizes flour based on water absorption (remember: higher protein flours are more absorptive), and it ranges from 90, for low-protein flours, to 370 or more for the most protein-rich flours.

In other countries, other scales, not related to protein content, are used to categorize flour. For instance, in France and Germany, their flour is assigned a number based on the ash mass left over after 10 grams (France) or 100 grams (Germany) of flour is incinerated. The Italians and Argentinians each have still a different numbering system. To assist with making flour substitutions from one country to another, this table provides a useful comparison of these different flour scales (Source: wikipedia.org). This article on hortuscuisine.com also provides a useful explanation of the W index and the Italian grading system.

In South Africa, cake flour and bread flour are readily available in supermarkets, with cake flour taking up about twice as much shelf space as bread flour. So-called "all-purpose" flour is not to be found here. In the US, all-purpose flour seems to be most common, with cake and bread flours being more specialized. Below is a photo of the typical flour lineup in Julia's local grocery:

Of the 21 spots occupied by wheat flours, 11 (about 50%) are all-purpose flours, either bleached or unbleached; two are cake flours; one is pastry flour; and one is bread flour. The remaining are either whole wheat or self-rising flours. Plus, there is another shelf, not pictured, dedicated to alternative, gluten-free flours and grains.

In the UK, "plain" flour (akin to US all-purpose flour), "strong" (aka bread), and self-rising flours are relatively common, though some report that UK "plain" flour tends to be weaker than US all-purpose flour. (Source: Doves Farm and Homepride; also, realbakingwithrose.com). In Belgium, the flour on the supermarket shelves seems to be mostly geared towards pastry/cake making. Bread flour is less common. In one instance there, a flour number was reflected on the package, but without any indication of which numbering system was used (Sources: Friends/family in Belgium).

This article by the famous American baker and cookbook author Rose Levy Beranbaum gives a glimpse into the difficulties that cross-country differences in flour can create for bakers. But the bottom line of her article (especially the comments at the end) and what I've said so far is: knowing the protein content of your flour will take out much of the guess work and help you make the best flour choice for your application.

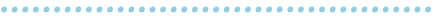

Fortunately, figuring out the protein content is usually pretty easy to do. In many countries, the protein content is listed under the nutritional information on the back or side of flour packages. Just divide the protein content per serving (usually in grams) by the serving size (also in grams), and you'll obtain the percent of protein in the flour - just what I reported in the table above.

POP QUIZ: What's the percent of protein in the flour shown below? And what type of flour do you think it is? (Please post your response in the comments below!)

Measuring Flour: To Weigh or Not to Weigh?

Another big difference across the world is how flour is measured. I have only ever known the metric system where recipes specify the weight of flour in grams. Recipes from the US, Canada, and the UK often measure flour by volume (i.e., in cups), not by weight. Julia says that, for whatever reason, scales are not a common kitchen tool in the US, and that most home bakers still favor cups for measuring. In fact, her US-based book publisher required that she use cup measures (to the exclusion of weights) in her book recipes for this very reason. That being said, even within the US, you'll see differences in how bloggers and cookbook authors cite their flour measurements. For instance, on her blog, Julia gives her flour measurements both by volume (cups) and weight (in both ounces and grams), so that her reading audiences everywhere can make easy translations. LilaLoa and Sweet Sugarbelle also provide both volume and weight measures, with the latter only in grams, whereas SemiSweet Designs only provides volume measures.

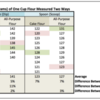

So is it better to measure by weight or by volume? And, if you need to make conversions between the two, how much does one cup of flour weigh? Let's start with the latter question, as its answer will help with the first question. It turns out that the weight of one cup of flour depends on many things: (1) the type of flour being measured (i.e., cake versus bread, with cake being the lightest); (2) the brand of flour (though usually to a lesser extent than flour type); (3) how the flour is handled before you measure it (i.e., do you sift it, or not?); (4) how you measure it (i.e., do you plunge the cup into the flour bin or spoon it in, and then level it, or do something else?), and (5) the actual cup measure! Yes, there are even variations in the size of one-cup measures from place to place. (More on that issue here!)

Stef from cupcakeproject.com took this question to a whole new level by weighing 192 cups of unsifted all-purpose flour! She found that measuring flour by the plunging (or dipping) method yielded 8.5% more flour by weight than did measuring by the spooning (or scooping) method. She further found a 7.3% difference between US flour brands, and a 2.2% difference across the sampling of measuring cups she had on hand. Julia did a less exhaustive, though similar, test in a recent YouTube video (starting at 4:07), which showed that the plunging method compacts flour more than the spooning method, yielding weights about 12% higher. She went further to show that, if you sift flour before measuring it, you'll decompact the flour and end up with less flour by weight (approximately 10% less) in your measuring cup.

For the fun of it, I took these ladies' leads and did my own weighing session, comparing the plunging and spooning methods using both unsifted Sasko cake flour and Gold Medal all-purpose flour. I measured between 7 to 10 cups in each case using the same metal, dry-foods measuring cup each time. The numbers show that all-purpose flour is slightly heavier than cake flour (by 2% to 3%), and that, for both flours, the weight of a plunged cup is about 12% heavier than the weight of a spooned cup, confirming Julia's results.

What does this all mean? It means that using volume (cup) measures is likely to yield much less consistent results than weighing your ingredients. In Julia's words, "Even small differences in the weight of flour in a recipe can have a large impact on the texture, spreading, and rising of many baked goods. If you don't own a scale, it's well worth the small investment! Weighing is always more accurate!"

An Experiment

Julia was kind enough to mail me a couple of bags of Gold Medal all-purpose flour, so I could compare US all-purpose flour to the cake and bread flours we have here in South Africa. I don’t know what the customs officials thought it was, but they opened the box and one bag, and surely took their time to come to a conclusion!

In all tests, I weighed all ingredients to eliminate the variability associated with volume measures, as discussed in the last section. Test A was my usual recipe (450 g cake flour, 200 g butter, 175 g icing sugar, 1 egg, salt and vanilla to taste, and no leavening) with my usual flour (see details below). And, in Tests B and C, I did one-to-one substitutions (by weight) of different flours for my usual flour. My primary motive behind these substitutions was to test the impact of differences in protein content.

But, since "all-purpose" flour is not available here, at least by that name, I was also interested in testing a couple of substitutions I found online (here, here, and here) for: (1) approximating cake flour with all-purpose flour (i.e., 1 cup cake flour = 1 cup less 2 tablespoons all-purpose flour plus 2 tablespoons cornstarch) and (2) approximating all-purpose flour with cake flour (i.e., 1 cup all-purpose flour = 1 cup cake flour + 2 tablespoons cake flour). These two substitutions were done in Tests D and E, respectively, assuming that 1 cup all-purpose flour, measured by the spooning method, weighs 4.5 ounces (128 grams), and 1 cup cake flour, measured the same way, weighs 4 ounces (113 grams). These cup equivalencies were drawn from online sources for all-purpose flour in the usual 9% to 12% protein range, and cake flour in the typical 7% to 8% range in the US. As demonstrated in my weighing test, my Sasko brand cake flour, which is 10.2% protein, weighed 123 g on average, so perhaps it will behave more like Julia's Gold Medal all-purpose flour, and these substitutions will be moot?! But, let's see!

More specifically, I made five batches of dough according to my usual recipe, using the following quantity and type of flour in each case:

A: 450 grams (15.9 ounces) Sasko (South Africa) cake flour (my usual amount of my usual flour with 10.2% protein);

B: 450 grams (15.9 ounces) Gold Medal (USA) all-purpose flour (10% protein);

C: 450 grams (15.9 ounces) Snowflake (South Africa) bread flour (11.8% protein);

D: About 400 grams (14.1 ounces) Gold Medal (USA) all-purpose flour (10% protein) plus additional cornstarch to make a substitute cake flour (i.e., a lower protein "flour" in this case) per the suggested formula noted above; and

E: 450 grams (15.9 ounces) Sasko (South Africa) cake flour (10.2% protein) plus 55 grams (1.9 ounces) cake flour to make a substitute all-purpose flour per the suggested formula.

I rolled each batch of dough to both a 4 mm (between 1/8 and 3/16 inch) thickness and a 6 mm (1/4 inch) thickness, and cut out circles and scalloped squares, as I thought those shapes would best show if any spreading or uneven baking occurs. The results for both thicknesses of cookies were the same; the pictures show the 6 mm (1/4 inch)-thick cookies.

The results were remarkable and not along the lines I expected. I expected the highest protein dough (Test C) to be stiffer and drier and to spread less than all the others; and also to be less delicate. Yet I perceived little to no difference in the stiffness/dryness of the various doughs or in how they rolled. Test C appeared to have spread less than some of the others (especially Test D which had the lowest protein content), but when I put the cookies back to back, there was hardly any difference!

In fact, the biggest difference that I noticed was not between the lowest and highest protein doughs (Tests D and C), but between the South African and US flours, irrespective of substitutions. The US cookies (Tests B and D) had wrinkled surfaces and relatively flat bottoms, whereas the South African cookies (Tests A, C, and E) had smooth surfaces and hollowed/domed bottoms.

My family took a "blind" taste test (so they would not see the smooth/wrinkled surfaces of the cookies). They noted that the cookies with the Gold Medal all-purpose flour tasted saltier, and the one with extra cake flour (Test E) was more "doughy", as might be expected. I didn't ask them specifically about texture, as I did not want to influence their responses, but I personally noticed no differences in delicacy or crumb.

Now, what do I make of all of this? I can't explain why the US dough was more wrinkled, but perhaps it has something to do with the bleaching of the flour? (The Gold Medal flour I had was bleached, and I don't believe the South African ones were.) But, more importantly, I'm left wondering if I would have seen more dramatic differences in dough handling, spreading, and texture, especially between Tests C and Tests D/A, if I had used a lower protein cake flour (closer to the 7% to 8% in the US) and a higher protein bread flour. After all, the Snowflake "bread" flour and the Sasko "cake" flour both fall within the "all-purpose" protein range in the US. I also mixed my dough until the ingredients were just incorporated, and the cookies were all cut from the first roll of the dough. So, in each case, the dough was handled very minimally, and the gluten was likely not as fully developed as it could have been, for instance, if I had rolled out the dough a second or third time. Julia has also posited that the lack of leavening in my cookie recipe dampened any differences in spreading/rising (attributable to different flour use) that might have been more visible in a leavened dough. She further noted that sugar has a tenderizing effect, so the texture of recipes with a relatively high sugar content, like cookie dough, might be impacted less (than bread or pie crust, for instance) by one-for-one substitutions of flour types.

Experiment conclusions: For now, all I can say is that, apart from a barely perceptible difference in spreading between Tests C and D, the type of flour I used did not make that much difference in my recipe. I'd be interested to try lower protein cake flour (and higher protein bread flour) in the future, and to hear about others' results when they've made similar substitutions in their recipes. I'd also love to see a study about the impact of bleaching flour - maybe it would explain the wrinkled result?!

Flour Survey Results

As you may or may not know, a few weeks ago, Julia launched a flour survey here on Cookie Connection in order to better understand how your flour use in rolled cookies dovetails (or not! ![]() ) with what's been said here. (If you haven't yet taken this survey, we would love your input. Just click here.) If you click on this link, you can also see all of the results so far, but here's a quick summary . . .

) with what's been said here. (If you haven't yet taken this survey, we would love your input. Just click here.) If you click on this link, you can also see all of the results so far, but here's a quick summary . . .

Of the 292 respondents, 77% are from the US, and the vast majority (89%) most often use all-purpose flour in their rolled cookie recipes, followed by a paltry 3% who use cake flour. Interestingly, most people (60%) say they use their preferred flour type because their favorite recipe calls for it; another 35% give the reason that it's easiest to find in their local stores. A far smaller number (only 25%) cites a credible reason based on food science ("It makes my cookie dough easier to handle and more resilient"). A whopping 81% of respondents selected the correct answer when asked about the function of gluten in baked goods ("Gives dough strength and structure"), and most people (61%) knew that bread flour has the highest gluten content. However, people struggled with the "bonus question" (Q15: "How much does one cup of all-purpose flour weigh?"), which was added later, along with a prize to one randomly drawn winner for answering it correctly! While only 27% of its 172 respondents got the right answer, my hope is that, after the rest of you read this post, the correct response will be a snap! ![]()

That's all for this edition of Toolbox Talk! If you have any questions or observations, please place them in the comments below along with your answer to my pop quiz (again, it's under "Flour Around the World")! There won't be any prize for getting the right answer this time, other than the title of self-proclaimed Flour Goddess! ![]()

Liesbet Schietecatte, born in Belgium but permanently living in South Africa since 2005, accidentally found her way into cookie decorating in 2012. Grabbing moments in between her career as an archaeologist and being a mommy and a wife, Liesbet bakes Belgian biscuits like speculoos in the tradition of her grandmother’s family who were bakers for several generations, but she gets the most creative satisfaction from decorating with royal icing. She bakes and decorates for occasional orders and at times for a crafters' market, but mostly for the enjoyment and challenge of trying out new things. To honour her family's baking legacy, Liesbet uses the family name to give a home to her baking pictures on Facebook: Stock’s – Belgian Artisan Bakes.

Photo credit: Liesbet Schietecatte

Note: Toolbox Talk is a bimonthly Cookie Connection blog feature written by Liesbet Schietecatte that explores similarities and differences in cookie tools and ingredients from all over the world. Its content expresses the views of the author and not necessarily those of this site, its owners, its administrators, or its employees. Catch up on all of Liesbet's past Cookie Connection posts here.

Comments (6)