Icing sugar lies at the base of cookie decorating, be it with royal icing or glaze or buttercream. It was through Cookie Connection host Julia Usher’s comments about her teaching experiences in other countries that I realised that icing sugar isn’t the same all over the world. She's reported that it can be much grittier outside the US, particularly in South America and to a lesser extent in Asia: "In some places, I can feel large sugar granules when I rub the sugar between my fingers, or hear them scratching against the sides of the bowl when I stir, which is nothing I've ever experienced with my powdered sugar in the US. Needless to say, this grit wreaks havoc on intricate piping." Our ongoing Cookie Connection icing sugar survey has revealed coarseness issues in Russia too.

I am so happy that, here in South Africa, I haven't had to contend with a gritty sugar texture, which can clog piping tips and be very frustrating.

In this Toolbox Talk, I've primarily tried to understand differences in icing sugar texture across the world by exploring how it is processed and graded by particle size. As a bonus, I've also examined the effects of anti-caking agents in icing sugar and your responses to our survey. [EDITOR'S NOTE: If you haven't yet filled out our survey, please do so here!]

How Icing Sugar is Made and Used

In essence, icing sugar is primarily (about 97%) white granulated sugar, made from either sugar cane or beets, ground to a very fine texture. In current practice, granulated sugar is fed into sugar mills that grind the sugar into one product (coarseness) at a time. Today's mills are typically of two types: some grind the sugar by pushing it against fine-mesh screens until it is small enough to pass through the screen openings, and others use cyclonic action to throw the crystals against the wall of the mill to shatter them. In the latter case, the ultimate particle size (product type) is controlled by the speed of the mill, the feed rate of the sugar into the mill, and retention time in the mill. [Sources: Imperial Sugar Company and Domino Foods interviews.]

Icing sugar is used in instances where the sugar needs to dissolve easily and quickly, or where it is important to get a smooth result - as in cookie decorating, of course! But the drawback of its powdery texture is that the sugar readily absorbs moisture and clumps. That is why corn flour (aka corn starch), potato starch, tricalcium phosphate (a calcium salt), or maltodextrin is usually added in small amounts as an anti-caking agent.

Names and Brands Around the World

Icing sugar has several names around the world, but those names do not necessarily imply different product characteristics. For instance, icing sugar is more commonly called "confectioner's sugar" in the eastern US, and "powdered sugar" in the western US. The literal translation from Dutch would be "flour sugar" (bloemsuiker), and from French, it would be "sugar you can’t feel" (sucre impalpable).

Before I get into differences in product characteristics, it's useful to understand branding within your country or region, as different brands may actually be the same product. For instance, in South Africa, there are 14 sugar mills, 11 of which are owned by three companies who market icing sugar under their own brands: Selati (made by RCL Foods, formerly Tsb Sugar RSA Ltd.), Illovo (made by Illovo Sugar Ltd.), and Huletts (made by Tongaat Hulett Sugar Ltd.). Three other companies own one mill each. [Source: South African Sugar Millers' Association.] Yet we have many more private-label brands in our supermarkets and cake supply stores, which means many of these stores are sourcing from the major suppliers. For example, Selati also supplies two large South African supermarkets: Woolworths and Pick n Pay. [Source: RCL Foods/Selati interview.]

Similarly, in the US, Domino Foods (part of ASR Group, which is the world's largest cane sugar refiner) markets both C&H and Domino brands of icing sugar. C&H is refined in California, and Domino is refined on the east coast, largely to the same specifications. In Belgium, the local Tiense Suikerraffinaderij brand of icing sugar is actually supplied by the German holding company Südzucker, which also supplies sugar to Germany, Bosnia, France, Moldova, Poland, Austria, Romania, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Hungary.

Conclusion: If you change brands hoping to get a different product, don't be surprised to find that your new brand is what you've always been using, just marketed differently! Doing a little research, by emailing or calling manufacturers as I did, can often clarify the true origin of your sugar.

Product Characteristics Around the World:

Particle Size and Anti-Caking Agents

As suggested earlier, icing sugar coarseness (or its average particle size) and its coarseness grading, or lack thereof, seem to differ the most across countries, and even within them. In eastern parts of the US, icing sugar coarseness is typically graded on an X-scale, but this same X-scale is not used in the western half of the US, or in any other part of the worId, as far as I can gather. So, while you can find a reference to "10X", for instance, on Domino icing sugar packaging, you will not see that same reference on C&H packaging. [Sources: Domino, Imperial, and other interviews/websites.] Sugar refiners (aka millers) in other parts have other ways of measuring and conveying sugar coarseness, which I will come to in a bit.

First, more on the X-grading scale used in the eastern US . . . It seems that X-grading is a historical remnant from the days when regular sugar was put through mills several times to obtain a finer icing sugar. The scale ranged from 1X to 14X sugar, where the number indicated how many rounds of grinding the sugar had undergone (with 14X being the finest sugar, of course). These days, granulated sugar is only processed once to make it into icing sugar (as described above), and the X-grades (if you see them) typically refer to particle size, either expressed as a distribution or range (with an average particle size and standard deviation) or as a percent of particles that pass through (or do not pass through) mesh screens or sieves of different sizes.

Unfortunately, just as the use of X-grading is inconsistent from place to place, so too are the definitions of each grade when they exist. For instance, Domino Foods defines its 10X grade as one where 97 percent of the sugar particles pass through a #200 mesh screen (with 74 micron-wide openings, with a micron being one-millionth of an inch). In other words, 97 percent of the sugar particles are 74 microns or less. Imperial Sugar Company, on the other hand, says its 10X grade has an average particle size of 60 microns with a standard deviation of 50 microns, meaning the majority of particles range between 10 and 110 microns within the same grade or bag of icing sugar. (BTW, not all 14 sugar grades are produced in the US any longer. The most common grades are 4X, 6X, 10X, and 12X, with 10X being what is typically sold as powdered or confectioner's sugar in retail stores. The other grades are usually reserved for commercial customers and applications.)

So how do companies in other parts of the world describe their icing sugar coarseness if they don't use X-grades? Essentially, they use the same mesh pass-through or particle size-distribution measures, which they publish and provide in product specifications upon request. (In the attachments below, you'll find examples of product specs from two companies - British Sugar in the UK and Nordic Sugar found in Denmark, Sweden, and other European countries.) With the exception of South Africa where there are national maximum particle size standards for icing sugar, the measurements and threshold particle size requirements vary across companies and countries, making immediate comparisons as challenging as within the US.

But have no fear! I have made the comparisons easy for you! I gathered all of the spec sheets and interview notes I could find, and expressed each company's (or country's) icing sugar specifications in roughly the same terms (i.e., particle size distribution). Then, using the Domino X-grades as a guide, I loosely associated each sugar with an equivalent X-grade to help with at-a-glance comparisons. You'll see these results in the table below:

(Microns)

Notes:

(1) 1 micron = one-millionth of an inch

(2) > = “greater than”; < = “less than”

(3) “Typical (USA)” refers to US industry figures reported in Sugar: A User’s Guide to Sucrose by Neil L. Pennington and Charles Walker, 1990. "Typical (South Africa)" refers to the South African Bureau of Standards Directive SANS 1145:2007, which states a maximum allowable particle size distribution for icing sugar marketed in South Africa.

(4) Nordic Sugar produces a wide range of icing sugars. I have only included three of their grades in the table above, ranging from most coarse ("Decoration") to least coarse ("Coarse" and "Extra Fine"). They have other grades in between.

Conclusions: While I was unable to obtain particle size data for South America, Asia, or Russia (where Julia and our survey highlighted the greatest coarseness issues), the above information suggests that Nordic Sugar's "Extra Fine" and (ironically) "Coarse" grades are perhaps even finer than the finest 12X grade in the US. Conversely, Nordic Sugar's "Decoration" grade, Südzucker, and typical South African brands seem to be among the coarsest for which I had data, possibly even coarser than Domino 4X.

The latter result is a bit surprising to me, as I have had no issues with grittiness in royal icing (touch wood) in South Africa. Tom Wilson, Director of Quality, Food Safety, and Technical Services at Imperial Sugar Company (US), mentioned that sugar grit typically becomes palpable at particle sizes of 150 microns, but perhaps there are simply too few particles of that size (less than 2%) in South African sugar to cause trouble. Or perhaps South African manufacturers are actually milling to finer levels than the maximum threshold indicated in their national standards. In the absence of spec sheets for South American, Asian, and Russian sugar, I can only assume that the brands used by Julia and others in these places are even coarser than the "<4X" sugars listed above.

If your sugar is creating problems due to grit, then review the product specs of available brands, and select a finer one, or give yours a whir for a minute or two in a food processor. Julia reports that processing the problematic South American sugar helped, but didn't completely prevent the plugging of tiny tips.

________

The other element in icing sugar is the anti-caking agent whose function is to prevent clumping by: 1) absorbing moisture when the icing sugar is exposed to humid air and 2) reducing direct contact between the sugar crystals. In finer icing sugar like 12X, there is more particle surface area and, so to accomplish the second point, the amount of anti-caking agent is often increased. In those cases, maltodextrin is sometimes used rather than corn or potato starch or tricalcium phosphate (TCP), as apparently it leaves a less starchy taste in larger quantities. [Source: Imperial interview.]

As with the particle size data, I collated all of the information I could find about the type and amount of anti-caking agent added to icing sugar to allow for easier comparisons:

(Percent by Weight)

Note:

(1) “Typical (USA)” refers to US industry figures reported in Sugar: A User’s Guide to Sucrose by Neil L. Pennington and Charles Walker, 1990. "Typical (South Africa)" refers to the South African Bureau of Standards Directive SANS 1145:2007, which states a maximum amount of additives (i.e., starch) for icing sugar marketed in South Africa.

Conclusions: With the exception of Nordic Sugar and 12X icing sugar (only available for commercial use in the US), the type and quantity of anti-caking agent used in icing sugars available for retail seems relatively standard across countries (3% corn starch). [EDITOR'S NOTE: That being said, I would also assert that perceived differences in clumping probably have less to do with differences in anti-caking agents and more to do with packaging and exposure of the sugar to humidity.]

Some Experiments

I did three experiments with brands of icing sugar available to me in South Africa: (1) I compared the look and feel of different icing sugars, to gauge relative coarseness; (2) I piped with royal icing made of these same sugars, again to gauge relative coarseness; and (3) I tried to figure out which, if any, of these sugars has the most anti-caking agent.

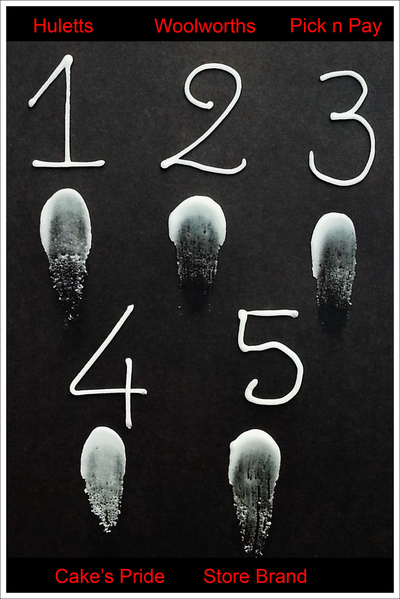

I tested five brands, including: (1) Huletts (manufacturer's brand, sold in a re-sealable plastic packet), (2) Woolworths (private-label supermarket brand sourced from Selati, sold in a re-sealable plastic packet), (3) Pick n Pay (private-label supermarket brand also sourced from Selati, sold in a paper packet), (4) Cake’s Pride (another private-label brand, source unknown, sold in a plastic bag), and (5) a cake supply store brand (again, a private-label brand of unknown source, sold in a plastic bag). Given that at least two of these five brands came from the same producer (Selati) and that South Africa has national particle size and anti-caking agent standards, I didn't expect to see many differences in the performance across these brands. But here's what I found . . .

1. Look and Feel Test: Four out of the five sugar brands tested looked smooth and fine-grained (see image below). Only the Pick n Pay brand looked lumpy. However, the lumps in the Pick n Pay sugar broke very easily, and that sugar was just as soft as the other brands.

2. Royal Icing Test: I did not feel any textural differences in the royal icing made with the different icing sugars. In the picture below, you will see that the icing "smears" also look virtually the same in all five cases, with no visible sugar granules. I also made stiff icing out of each sugar, and piped it (into the numbers shown below) using a paper cone with a very small opening (about 1mm, equivalent to my #00 metal tip). None of the tips blocked while piping these letters, though, admittedly, they were small letters (about 4 cm/1.5 in). Icing #5, made with the cake supply store brand, was thicker than the rest, which is why that number is a bit more wobbly!

3. Anti-Caking Agent Test: In a cake demo about royal icing a few years ago, the instructor described a way to test for the relative quantity of anti-caking agent in icing sugar. Dissolve some sugar in water and, if the water becomes white and "milky", a lot of starch was added. Conversely, if the water stays reasonably clear, there is very little anti-caking agent in the sugar.

Granted, this test is based solely on visual observation, and isn't very scientific! And, again, South Africa has national standards that specify a maximum quantity of additives (3%) for icing sugar, so I didn't expect to see much difference across brands. But I carried on nonetheless! (Who doesn't love a good experiment, right?!)

For this test, I added 1 tablespoon of icing sugar (of each brand) to a half cup of water (250 ml or 8.5 fl oz). I first left the sugar to dissolve on its own. I then left the glasses to stand for two hours, so the sugar could settle.

When I left the sugar to dissolve, the Pick n Pay solution turned the least white, followed by Woolworths. Cake's Pride, Huletts, and the cake supply store brand tied for third as most milky. But the differences were small, as shown below.

I have no photograph of what the glasses looked like after leaving the sugar to settle for two hours, as ants had taken over! However, I did struggle to get the settled Pick n Pay sugar out of its glass, as it had almost solidified in this time. The other sugars were easier to remove.

Conclusions: It seemed that the Pick n Pay sugar stood out in three ways: (1) it was the only one packaged in a paper bag as opposed to plastic; (2) it was the lumpiest; and (3) it created the least milky water and the most stubborn sediment, both of which could be indicators of having less anti-caking agent. Now, the lumps can probably be explained by its paper packaging, which is less resistant to humidity than plastic packaging. But, seeing as Pick n Pay sugar is the same as Woolworths sugar (both produced by Selati) with the same anti-caking agent and quantity (3% corn starch), I can't really explain the third result. (I even double-checked the anti-caking agent and quantity with the manufacturer.)

Your Experiences with Icing Sugar

So what brand(s) of icing sugar do you use and how happy are you with your choices? Julia and I found out by asking Cookie Connection visitors to fill out this survey. (Again, we're continuing to collect data, so please fill it out if you haven't already.)

Brands Used: Of the 161 people who had responded by the time of this post, about 73% were from the US. And among those respondents, Domino is the favored brand (37%), followed by C&H (25% ) and Imperial (11%). The remaining 27% of US respondents primarily use (presumably) less expensive private-label brands from Walmart, ALDI, Kroger, Costco, Sam's Club, or other local stores. Cookiers in other countries use their own local brands, with Redpath and Rogers (both Canadian) being the only brands mentioned more than once.

Sugar Grades Used: 47% of respondents stated that they use 10X icing sugar, and another 47% said they didn't know the grading. These results are not surprising considering that most respondents were from the US, where the leading brand of icing sugar in the eastern half of the country (Domino) has "10X" indicated on the packaging, and the leading brand to the west (C&H) does not. Some C&H users assumed this brand is also 10X, because of its fine texture - and these users were right!

Brand Satisfaction: Overall, cookiers are relatively happy with their primary brand of powdered sugar, with about 75% rating their satisfaction a 4 or 5 on a five-point scale. Of the 25% (36 people) who were moderately or less than satisfied, the biggest reasons for this dissatisfaction were grittiness (18%), followed by lumpiness (13%) and expense (12%). About 70% of respondents have also changed primary brands at one time or another, for reasons that largely parallel the reasons for dissatisfaction - i.e., too expensive (19%), too gritty (18%), and too lumpy (12%).

Summary

My research on icing sugar has been very interesting - though I wish I had been able to explain the coarseness issues experienced in some countries with concrete particle size data! [EDITOR'S NOTE: We still have some emails out to South American manufacturers, so perhaps that data will come in due time!] What I have learned is that, within my country, different brands seem relatively similar in quality, probably because of our national standards. Also, the largely American Cookie Connection respondent pool is quite satisfied with the quality of their sugar.

I would love it if cookiers from South America, Asia, Russia, and other places could share their experiences with us below, or maybe contact a sugar mill in their area to get the particle size of the sugar they're using!

Acknowledgments

I must acknowledge the help I got from so many people and sources to complete this post:

In the US: Thank you to Julia for collating information from the following sources: Tom Wilson, Director of Quality, Food Safety, and Technical Services at Louis Dreyfus Company (Imperial Sugar Company); the marketing team at Domino Foods; and Cheryl Digges, VP Public Policy and Education, The Sugar Association. Also, Sugar: A User’s Guide to Sucrose by Neil L. Pennington and Charles Walker, 1990.

In South Africa: Greg Beyers, SHERQ (Safety, Health, Environment, Risk, and Quality) Manager, RCL Foods (Selati); Wayne E. G. Jayes, Freelance Sugar Engineering and Project Management Consultant at The Sugar Engineer; and the Huletts Call Centre. Also, South African Sugar Millers' Association.

In Belgium: Bart Sintobin, Retail Sales Assistant at Tiense Suikerraffinaderij.

Liesbet Schietecatte, born in Belgium but permanently living in South Africa since 2005, accidentally found her way into cookie decorating in 2012. Grabbing moments in between her career as an archaeologist and being a mommy and a wife, Liesbet bakes Belgian biscuits like speculoos in the tradition of her grandmother’s family who were bakers for several generations, but she gets the most creative satisfaction from decorating with royal icing. She bakes and decorates for occasional orders and at times for a crafters' market, but mostly for the enjoyment and challenge of trying out new things. To honour her family's baking legacy, Liesbet uses the family name to give a home to her baking pictures on Facebook: Stock’s – Belgian Artisan Bakes.

Photo credit: Liesbet Schietecatte

Note: Toolbox Talk is a bimonthly Cookie Connection blog feature written by Liesbet Schietecatte that explores similarities and differences in cookie tools and ingredients from all over the world. Its content expresses the views of the author and not necessarily those of this site, its owners, its administrators, or its employees. Catch up on all of Liesbet's past Cookie Connection posts here.

Comments (24)